APAW Week 4: Trying Zig

For week 4 of my ‘A Project A Week’ series I decided that I would try learning Zig, a low-level programming language with compile time metaprogramming.

Why Zig?

I chose Zig because at work I have been in the need for a better webcam virtualisation driver, and I have been evaluating writing one myself. Traditionally this would be done in either C or C++, using the win32 api. Zig presented a promising alternative to C however, as it made a number of design choices that are better in hindsight relative to C:

- No preprocessor or macros

- A package manager by default

- A build system by default

- Unit testing by default

- String slice types and other memory safety features

Zig also has a number of killer features that allow more elegant expression of programs such as:

The Good

Compile time metaprogramming

This is good for a variety of features, such as precalculating expensive calls and handling build targets

fn multiply(a: i64, b: i64) i64 {

return a * b;

}

pub fn main() void {

const len = comptime multiply(4, 5);

const my_static_array: [len]u8 = undefined;

}

Defer

This is great for certain patterns of code, such as cleaning up memory after a function

try network.init();

defer network.deinit();

The ability to include C headers directly

This makes wrapping C libraries an easy pleasure

const rl = @cImport(@cInclude("raylib.h"));

The ability to use the zig compiler as a C compiler

This feature helps transition from C codebases to using Zig in a smooth way

zig cc main.c

The Bad

Zig has a lot of issues, so many that it killed my initial excitement and convinced me that it’s not a production-ready language yet

Poor Documentation

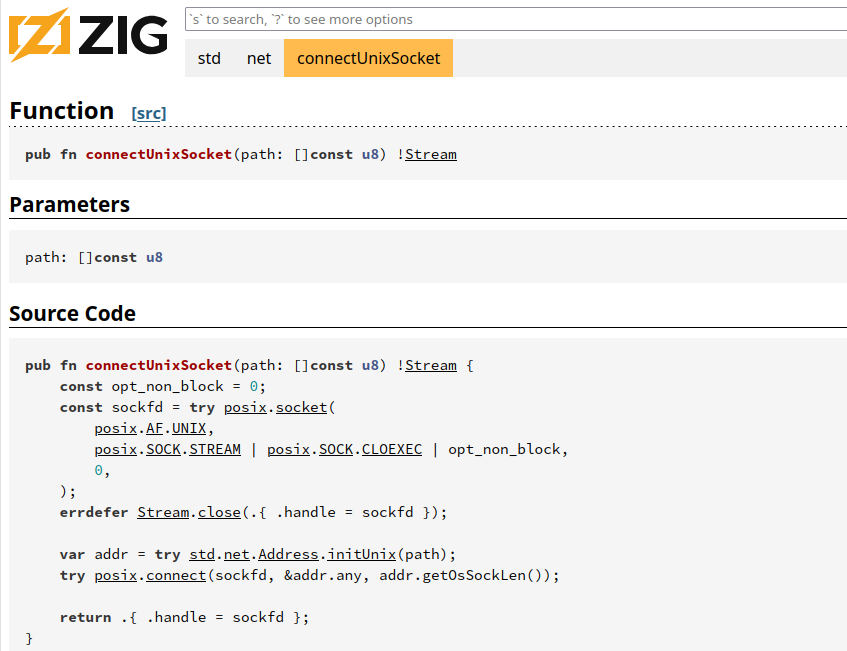

Zig is poorly documented, with the documentation being little more than a few sentences at best for any given set of functions, with no descriptions of important information. For example on documentation for std.net:

The array of []const u8 doesn’t provide clarity that we are seeing a networking path spec and the documentation explains nothing about the function, forcing the user to experiment with the api to find its precise function. This would be fine for niche parts of the standard library but it is the case for almost all of it, severely slowing down development time.

Too Much Change

Zig changes a lot, and fast. That’s fine, but it stops it from being usable in production. Furthermore when, how and why things are changed is very poorly documented. I began writing a network scanner (think nmap) in Zig, and upon googling found zig-network, which had an issue about making it part of the standard library. I began writing code leveraging it, as other resources said that std.net was still in development. As it turned out however, std.net was already released, just barely discussed online and mentioned on no major pages on UDP socket networking in Zig, leading to me incorrectly using an outdated and unecessary library to write my program.

The Build System

Zig’s build system isn’t terrible but it features some weird decisions. The main one among them is that there was an active choice to remove the command zig init-exe, which set up a zig project for building standalone executables; Instead the user must now run zig init, which generates tests, library code and executable code, and then remove unneeded components. This is frustrating and the choice to remove features that had a use case, rather than incorporate them into the new, better design decisions, leads to frustration.

VSCode Integration

For some reason the VSCode extension for Zig is particularly prone to issues. It would often highlight fake errors in my code, update slowly and take long pauses to check the code. Whilst not a dealbreaker its buggy nature further increased my frustration in working with the language.

Non-intuitive Design

I think this point is a bit of a loose one but to me Zig felt ‘unintuitive’ in its design, in that I couldn’t work out how to logically do or extend concepts e.g. with the following code

if (connectionSucessful) |value| {

std.debug.print("Port {d} is open", .{i});

} else |err| {

std.debug.print("Panicked at Error: {any} \n", .{err});

}

In it I unrwrap a variable connectionSuccessful and check if it’s an error, reacting accordingly. But when I wanted no error branch and to handle the error silently I couldn’t deduce how (or if it was even possible). None of the following were right and I never found what is:

// Idea 1

if (connectionSucessful) |value| {

std.debug.print("Port {d} is open", .{i});

} else |_| {

std.debug.print("Panicked at Error: {any} \n", .{err});

}

// Idea 2

if (connectionSucessful) |value| {

std.debug.print("Port {d} is open", .{i});

} else _ {

std.debug.print("Panicked at Error: {any} \n", .{err});

}

// Idea 3

if (connectionSucessful) |value| {

std.debug.print("Port {d} is open", .{i});

}

All of these would be intuitive syntax but none of them are correct for one reason or another, making simple error value discarding confusing. I know the response would be RTFM in most cases, but paired with Zig’s terrible documentation quality it’s easy to get a language-based roadblock

Closing Thoughts

Zig is undoubtedly an interesting language, and in line to potentially truly succeed C. It learns from C’s mistakes well and integrates nicely with existing C codebases. However, it is simply not ready for production or general use yet, and needs a few more years of work for me to consider using it for a real project. Its use of LLVM also might kill its place as a C successor due to it limiting portability. Only time will tell though, but for now Zig has proven itself to be not ready for my use, and has been a disappointment and handicap in working on my project for this week.