Reverse Engineering Java Programs For Fun And (Mental) Profit

Introduction

In my spare time I sometimes play a video game called ‘Slay the Spire’ with my friends. It’s a card game where you go through different encounters in a map and fight enemies, tackle events and buy items to gradually build up a better deck that can face the tougher challenges the game throws at you over time.

By default the game actually doesn’t have multiplayer, instead we use a mod called ‘Together in Spire’ (yes it’s spelt that way). This mod adds skins to the game to allow the players to differentiate each other if they play the same character, but some of these skins are locked behind special events or challenges, and can only be accessed via entering codes.

In this article I’ll detail how I reverse-engineered the game, written in Java and using LibGDX, to unlock every skin for me and my friends, so we could have more fun.

Tracking Down The Jar File

The first step to any reverse-engineering is obviously to find the file we want to look at!

Luckily in this case it’s fairly easy, as the mod is installed via the gaming platform Steam. To find the mod we can go to where steam stores all its mod downloads, which can be found by going to the games folder and going up two directories (Or just going to ~/.local/share/Steam/steamapps/workshop/content/ on Linux).

Then to find the game we need its ID, which every game on the platform has. This can be found by searching on SteamDB or simply by looking at the URL of the store page. In our case the game ID is 646570. Similarly we can then find the folder for the mod by looking at its url, in this case it is 2384072973. Navigating to this folder we find TogetherInSpire.jar, our target.

Opening The Jar

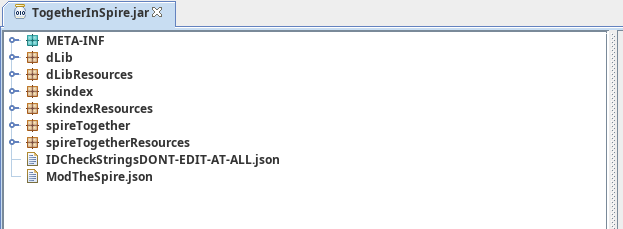

A jar file is just a glorified zip file, but the contents are all Java bytecode of the original classes so we need something to decompile them back to readable Java code. For that I chose to use ‘jd’, a popular Java decompiler. Opening the jar we found earlier we are presented with this:

Finding Our Class

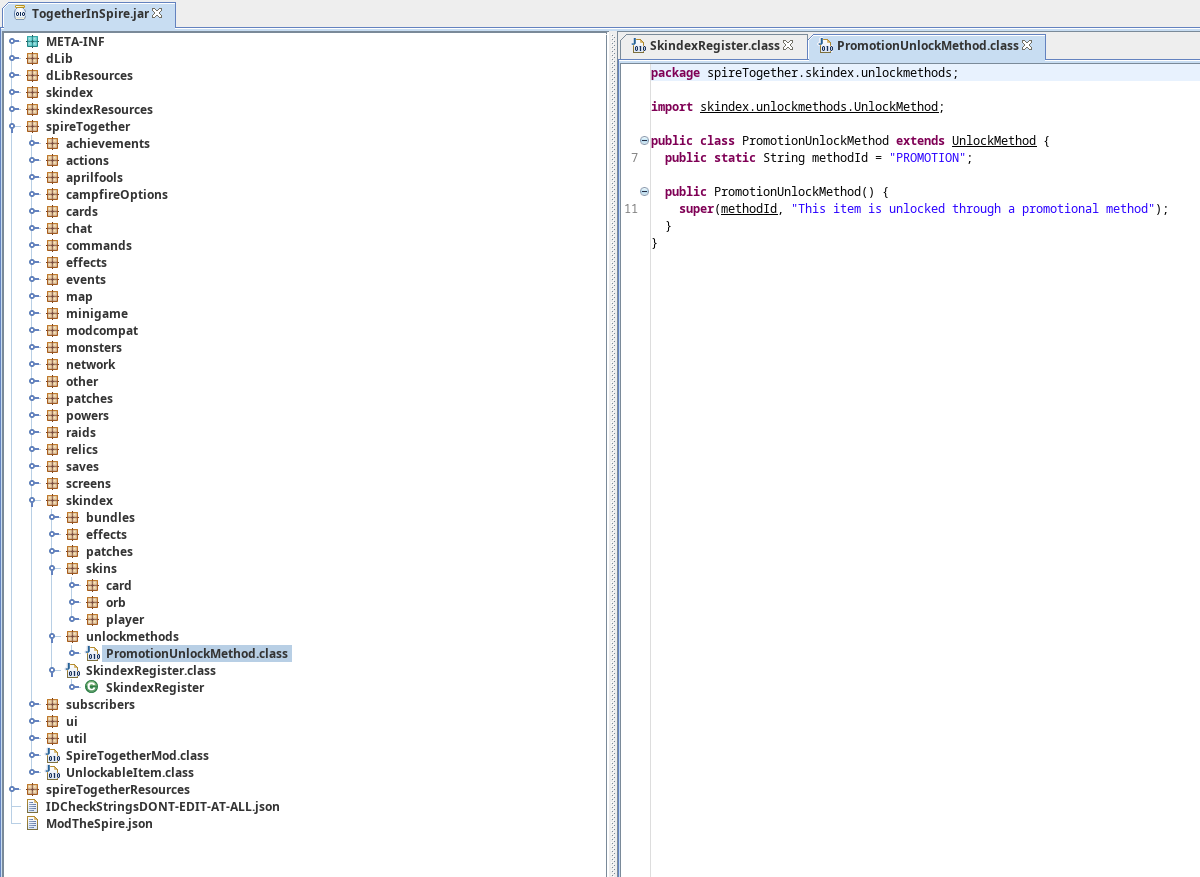

Finding what we need in a foreign codebase can take some time, so I began by simply looking through relevantly named files to get an idea of the games structure, finding classes for unlock methods and more in two separate skindex packages.

After enough looking around I eventually found ‘spireTogether.other.CodeManager’, the class that handles validating codes and their contents to choose what to unlock. From here the only thing to do is trace the parsing code to find out the best ones and the skins are ours.

How The Codes Work

Codes are first handed off to a method called ‘RedeemCode’ which checks for a special header ‘STSCD’ that all codes must be prefixed with. Then a single character determines the type of things to unlock (S for skin, B for bundle and most promisingly M for special codes).

public static Result RedeemCode(String c) {

if (!c.startsWith("STSCD"))

return Result.INVALID;

if (c.length() > 5) {

c = c.substring(5);

char type = c.toCharArray()[0];

c = c.substring(1);

switch (type) {

case 'S':

if (c.length() == 8)

return RedeemSkinCode(c.substring(0, 5), c.substring(5));

break;

case 'N':

return RedeemNameplateCode(c);

case 'U':

return RedeemUICode(c);

case 'P':

return RedeemPatreonCode(c);

case 'M':

return RedeemSpecialCode(c);

case 'A':

return RedeemAchievement(c);

case 'B':

return RedeemBundle(c);

case 'C':

return RedeemCursor(c);

}

}

return Result.INVALID;

}

After this the code is handed off to a specific method for parsing. Let’s look at how bundle codes are parsed first since they’re the simplest.

public static Result RedeemBundle(String UUID) {

for (Bundle s : SkindexRegistry.getAllBundles()) {

if (DevConfig.isDeveloper)

SpireLogger.Log(s.id + " - STSCDB" + (10000 + (new Random(s.id.hashCode())).nextInt(90000)));

if (UUID.equals(String.valueOf(10000 + (new Random(s.id.hashCode())).nextInt(90000)))) {

if (Unlocks.Get().unlockBundle(s))

return Result.REDEEMED;

return Result.DUPLICATE;

}

}

return Result.INVALID;

}

As we can see first there’s a check for if the mod is in developer mode, which just logs the code entered.

if (DevConfig.isDeveloper)

SpireLogger.Log(s.id + " - STSCDB" + (10000 + (new Random(s.id.hashCode())).nextInt(90000)));

Then there is a check that the code we entered (with the prefix STSCDB we discussed previously stripped) matches a specific set of code

String.valueOf(10000 + (new Random(s.id.hashCode())).nextInt(90000))

This system is a slightly poor way of obfuscating the codes contents. Effectively a special number is generated using this code, and is made to give similar codes unique bodies (e.g. bundle 1’s code might be STSCDB81353 and bundle 2’s might be STSCDB43712, making it hard to visually reverse-engineer the codes)

- s.id is the ID of the bundle we are unlocking

- (new Random(s.id.hashCode())).nextInt(90000) simply creates a randomizer, seeded with the bundle id, and then generates an integer from 0 to 90000, to become the body of the code after STSCDB

Summary Of The Code Structure

In summary a code, such as STSCDB81353 can be broken down into:

- A magic header that’s always present (STSCD)

- A special character dictating the code type (B for bundle in this case)

- A body set of numbers, always 90000 or below, that is a form of hash of the id of the thing being unlocked

Unlocking Everything: The Master Code

Unlocking every skin one by one using codes would be very tedious so we need a faster way. Luckily there’s a code type we haven’t talked much about yet, called ‘Special’, prefixed with an M. If we look at the body of ‘RedeemSpecialCode’ we see something quite interesting:

public static Result RedeemSpecialCode(String UUID) {

if (UUID.equals(String.valueOf((new Random("MASTERKEY".hashCode())).nextInt(90000)))) {

if (!(Unlocks.Get()).hasMasterKey) {

Unlocks.Get().UnlockMasterKey();

return Result.REDEEMED;

}

return Result.DUPLICATE;

}

return Result.INVALID;

}

Notice in this case the body is generated from hashing a keyword “MASTERKEY”. This gives us a bit of a hint about what this key might do, since we know a master key usually means something that unlocks everything, including skins. So to find the code we can simply reverse the code parsing process and make our own java program to calculate the valid master key code:

/* Special Code (Master Unlock) */

System.out.printf("STSCDM"); // Print the header

System.out.println(String.valueOf((new Random("MASTERKEY".hashCode())).nextInt(90000))); // Generate the body

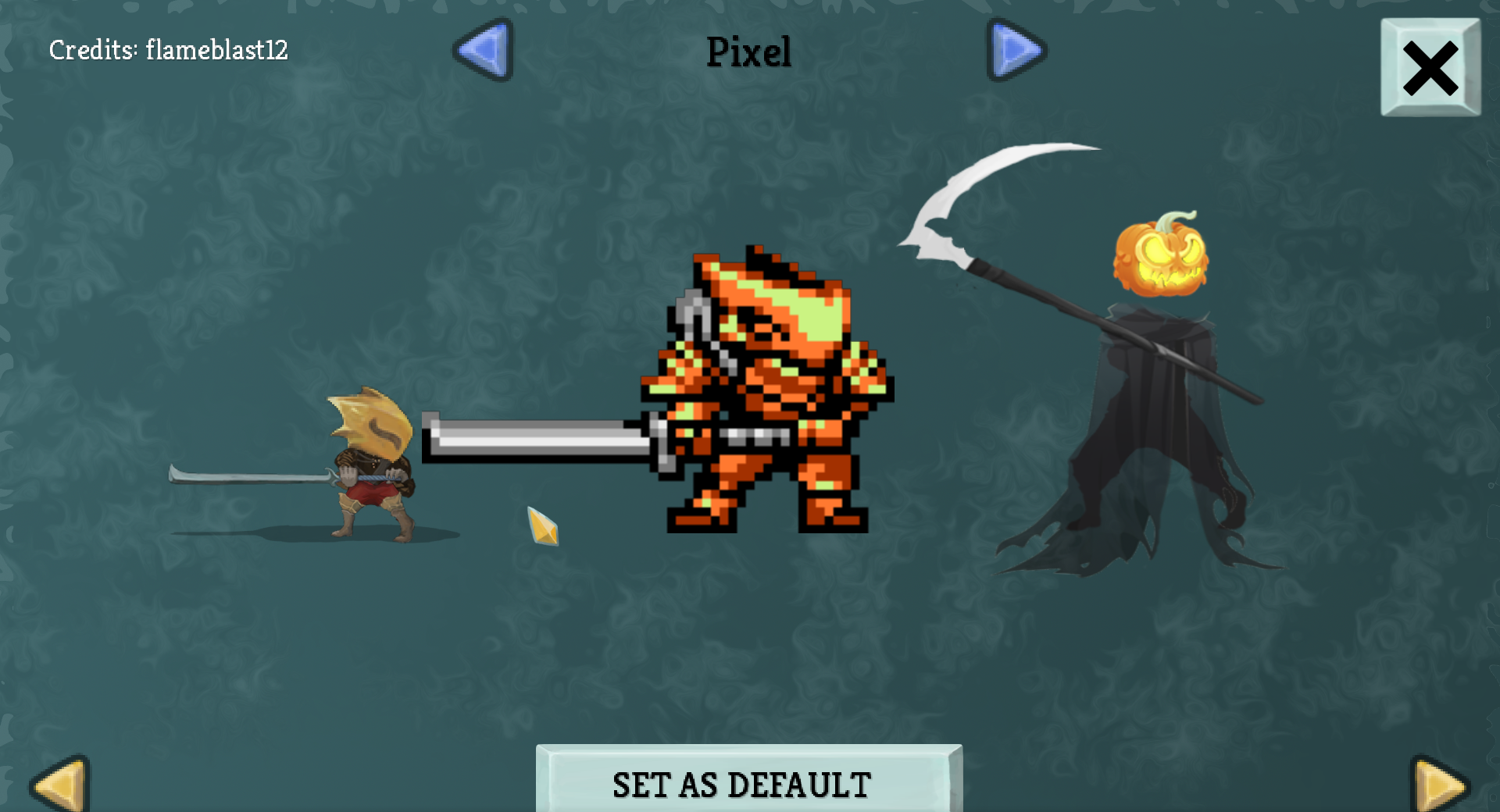

This program prints the special header without a newline (STSCD and M for the special or master code type). Then it prints out the hashed body used to check a master code is valid, producing the code in its entirety. Running it we get ‘STSCDM13295’. If we input it into the master code into the game we can see the results:

And indeed, going back to the previously locked skins we can now see they are all unlocked for our use!

Conclusion

Reverse-engineering these codes was a lot of fun. It was fairly quick, since I discovered the locked skins at around 10pm after a long day and had them all unlocked by midnight. The result of it, that me and my friends had more skins to mess around with in a game we liked was very nice too, particularly since some of the skins (such as the Chibi ones seen to the left in the screenshots) are very goofy and make for a good laugh.

Reverse-engineering Java programs is really pleasant because like C# it uses reversible bytecode for error messages and other language features all symbols are retained even in shipped binaries, meaning that looking at and modifying Java programs through reverse-engineering is nearly as pleasant as having the source code itself (minus some optimisation losses and comments of course).