Writing A Forth In C++

Introduction

Forth is a procedural, concatenative, stack-oriented programming language invented in 1970 by Chuck Moore, an embedded systems programmer.

The language is famous for its simplicity, being possible to implement in a few hundred lines of assembler or C. Seeking to understand the language I implemented it in C++.

What We Are Building

A quick demo of the final result, defining and executing a function

A quick demo of the final result, defining and executing a function

The final project, which can be found here, features:

- Basic stack operations (Arithmetic & IO)

- Function definition support (Colon definitions)

- Disassembly functions (dis)

Basic Operations

Forth is most well known for its stack based design, so to start we define a stack and some common arithmetic operations:

#include <stack>

std::stack<cell_t> ds; // data stack

/* Basic Arithmetic */

void f_add() {

cell_t v1 = ds.top();

ds.pop();

cell_t v2 = ds.top();

ds.pop();

ds.push(v1 + v2);

}

void f_sub() {

cell_t v1 = ds.top();

ds.pop();

cell_t v2 = ds.top();

ds.pop();

ds.push(v2 - v1);

}

void f_mult() {

cell_t v1 = ds.top();

ds.pop();

cell_t v2 = ds.top();

ds.pop();

ds.push(v1 * v2);

}

void f_div() {

cell_t v1 = ds.top();

ds.pop();

cell_t v2 = ds.top();

ds.pop();

ds.push(v2 / v1);

}

Then we implement common manipulations for the stack arguments. ‘dup’ copies the top item of the stack, allowing us to reuse computations. With just dup and arithmetic it becomes possible to implement operations such as the quadratic formula. ‘swap’ swaps the top two items on the stack.

/* Stack Manipulation */

void f_dup() {

ds.push(ds.top());

}

void f_swap() {

cell_t top_val = ds.top();

ds.pop();

cell_t second_val = ds.top();

ds.pop();

ds.push(top_val);

ds.push(second_val);

}

The Dictionary

Forth stores all of the function definitions in a linked list known as the dictionary. Each entry of the dictionary is an ‘execution token’ (xt), describing a function and its name.

struct xt {

std::string name;

xt *prev;

std::vector<xt> data;

cell_t val;

void (*code)(void);

};

// For posterity we implement a linked list

// alternatives such as std::vector may be more suitable for practical uses

xt *dictionary;

The Main Loop

The main loop is part of what makes Forth so simple, we will start with defining the REPL loop

// Part of main

while (true) {

src = "";

std::cout << "> ";

std::getline(std::cin, src);

interpret();

}

Interpret just splits the individual words in the input by spaces, and then sends them for processing

std::string get_word() {

std::string w = "";

// if it's a string read the the whole thing

if (*src_pos == '"' && *src_pos != '\0')

{

w += '"';

src_pos++;

while (*src_pos != '"') {

w += *src_pos;

src_pos++;

}

w += '"';

}

else

{

// otherwise just read until we find a space

while (!(isspace(*src_pos)) && *src_pos != '\0') {

w+=*src_pos;

src_pos++;

}

}

if (*src_pos != '\0') { // we don't want to skip the eof and run off into random memory

if (*src_pos == '"') { src_pos++; }

src_pos++;

}

return w;

}

void interpret() {

src_pos = src.c_str();

std::string w;

while (*src_pos != '\0')

{

w = get_word();

interpret_word(w);

}

}

The core of Forth is the following function, called ‘interpret_word’ in our implementation, which simply processes words based on if they’re numbers or text

void interpret_word(std::string w) {

// string support, entirely optional and non-standard for Forth

if (w[0] == '"') {

w.erase(remove( w.begin(), w.end(), '\"' ),w.end());

std::string *temp_string = new std::string;

*temp_string = w;

ds.push((cell_t)temp_string);

}

else if ((current_xt=find(dictionary, w))) {

// xt in dict, run function

current_xt->code();

}

else {

char *end;

int number = strtol(w.c_str(), &end, 0);

if (*end) {

std::cout << "word not found: '" + w + "'" << std::endl;

}

else ds.push(number);

}

}

Notice how we run the ‘code’ function pointer from our earlier xt definition, this points to a function that tells us what to run e.g. add or sub. Part of the simplicity of Forth is that everything is a function, even numbers, which just push the data to the stack.

These elements bring the core of Forth, let’s write some extra definitions to add the functions we defined earlier to the dictionary for lookup by the interpreter before we finish.

// Takes a function and name and pushes a new xt to the dictionary

// the xt has the name supplied and the interpreter can now find it

xt *add_word(std::string name, void (*code)(void)) {

xt *word = new xt;

word->prev = dictionary;

dictionary = word;

word->name = name;

word->code = code;

return word;

}

// Bulk define the default primitives

void load_primitives() {

// Arithmetic

add_word("+", f_add);

add_word("-", f_sub);

add_word("*", f_mult);

add_word("/", f_div);

// Stack Manipulation

add_word("dup", f_dup);

add_word("swap", f_swap);

}

Functions & Compiling

There’s one final key feature we need, which is the ability to define our own functions. To do this forth uses a colon and ends functions with a semicolon e.g.

( Add two to the given number )

( x -- x ) ( <- this is a stack comment, describing the functions change to the stack )

: add2 2 + ;

The trick here is to define a function, called ‘docolon’ that executes our new definitions. It works by taking words in a list and executing them one by one until it finishes.

// function assigned to colon definitions, runs the xts in the data section

void f_docolon() {

for (xt foo: current_xt->data) {

foo.code();

}

}

Then we simply compile functions by using a ‘compile’ mode that defines new words, pushing other words into its data section until it sees a semicolon.

void f_colon() {

compile_mode = true;

definition_name = get_word();

}

In intepret_word we add at the start:

if (compile_mode) { return compile(w); }

Where compile simply pushes the word into the one currently being compiled, and is similar in form to interpret_word

void compile(std::string w) {

if (w[0] == '"') {

// we are reading a string, not a normal word

w.erase(remove( w.begin(), w.end(), '\"' ),w.end());

std::string *temp_string = new std::string;

*temp_string = w;

code.push_back(make_lit_xt((cell_t)temp_string));

}

else if ((current_xt=find(macros, w))) {

current_xt->code(); // if it's immediate we run it

}

else if ((current_xt=find(dictionary, w))) {

code.push_back(*current_xt); // if it's not immediate we compile it

}

else {

char *end;

int number = strtol(w.c_str(), &end, 0);

if (*end) {

std::cout << "word not found (compiling): '" + w + "'" << std::endl;

}

else {

code.push_back(make_lit_xt(number));

}

}

}

And then we define semicolon as so to finish the compilation, pushing the new word to the dictionary and resetting the current compiling word’s data:

void f_semicolon() {

xt *new_word = add_word(definition_name, f_docolon);

// need to set data section here

new_word->data = code;

code.clear();

// exit compiling

compile_mode = false;

}

Conclusion

With that we have all the elements of a fully-functional Forth, and can write basic programs to solve simple problems. By defining more builtins, and using hardware where memory access is more effective, this simple language can do great things.

Some Inspiration For Forth Projects

Starflight, a hit game in the 80s, was written in Forth

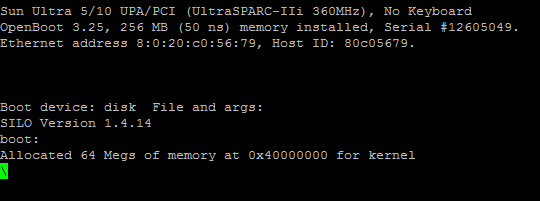

OpenBoot (later Open Firmware), a boot loader, used Forth due to its small size and relative abstractions