Programming Is Art

An essay defending our medium.

What Is Art?

What constitutes art has been up for debate for centuries. This is a fact which complicates this discussion, but I believe that under all major viewpoints programming qualifies.

Art As Method

Medium

Art as method is the idea that something is artistically valuable because of the way it was created, the difficulty of the product and its beauty from this effort. For example, arguably the (second) most famous art piece in the world is Michaelangelo’s ‘David’. The piece is revered not for what it depicts, but how it depicts it. The skill and beauty of carving a man from stone is the art, not just the resulting piece.

Michaelangelo’s David (Completed in 1504)

Michaelangelo’s David (Completed in 1504)

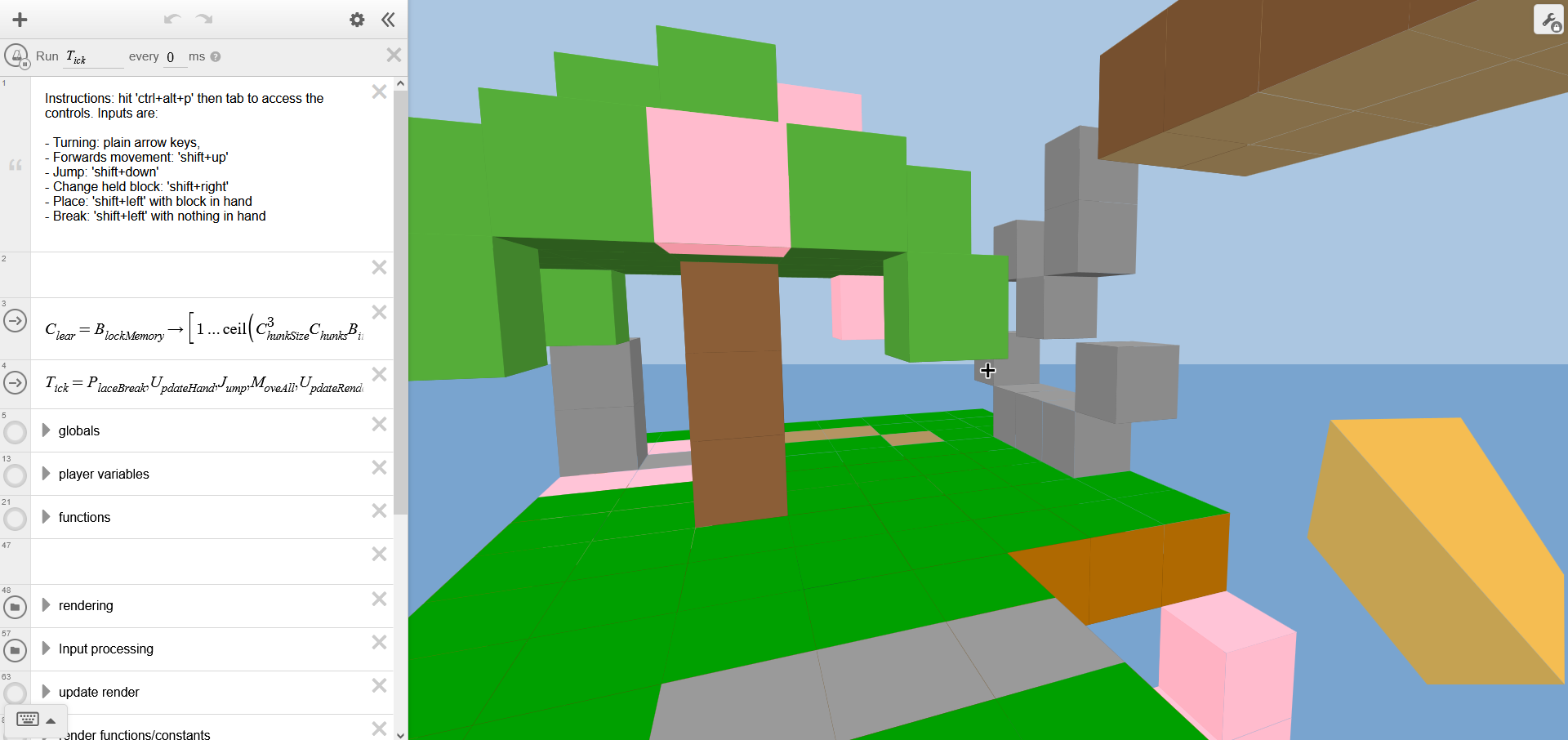

Does programming have a method? Of course it does, and some methods are more impressive than others. When people announce certain projects targeting hard platforms, or using difficult technologies, that is what makes the resulting product impressive. For example, when someone creates a clone of Minecraft in the graphing software Desmos, it is not the product, the game, that is impressive, it is the medium and result they produced with it.

Indeed demoscenes, programs designed to show art and how impressive it is, usually on older hardware, are largely about method. Below is Starstruck by the team Black Lotus, a demo that runs on the Amiga. Above it is a video of what many consider to be the ‘best holding up’ Amiga game. The idea that one is making a statement to the other, and about the medium on which it is made, is undeniable. (For best effect I suggest watching both on Youtube, in full resolution, in fullscreen).

Turrican 2, the best holding up Amiga game (according to the internet)

The Black Lotus’ Starstruck (2006)

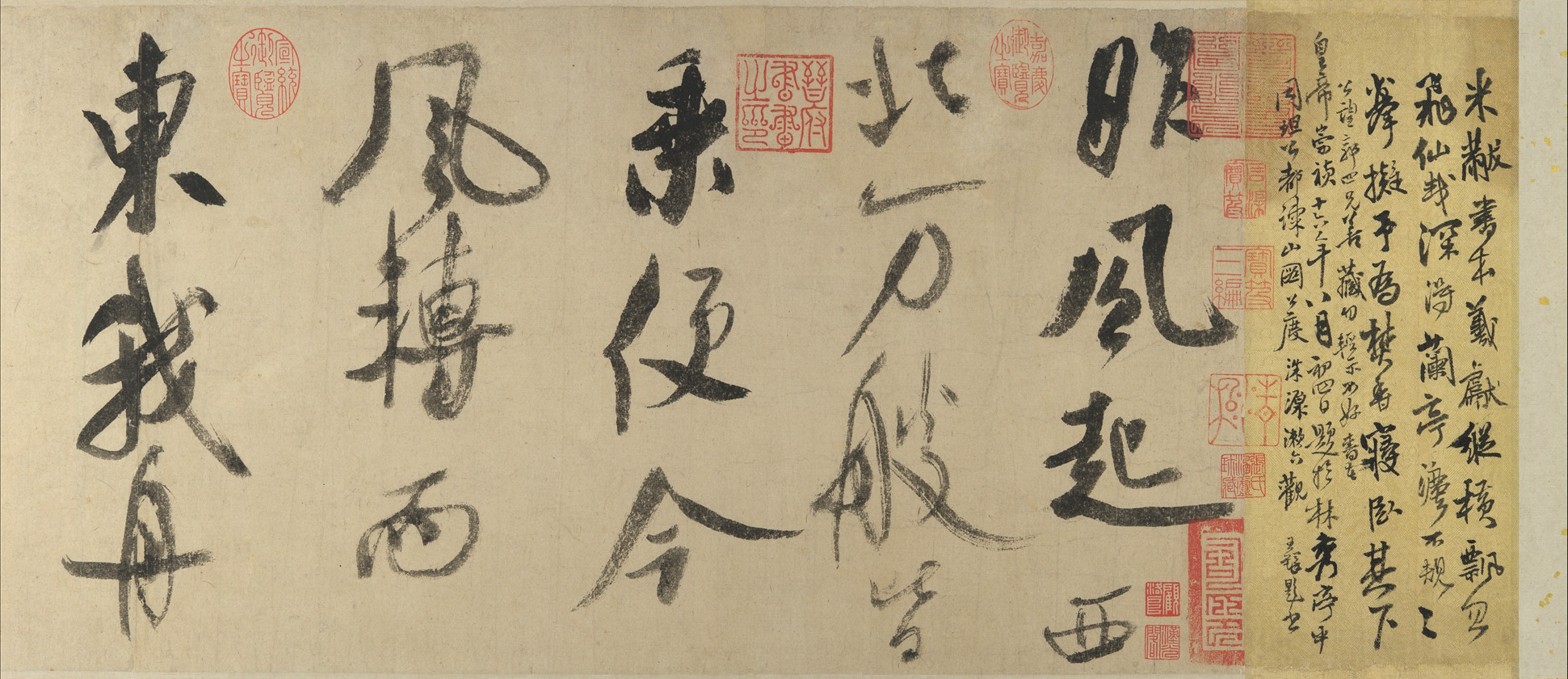

Form

Another key component of the view of art as a method is the expression of form, and what it represents about the artist. For example, one of the most famous pieces of ancient chinese caligraphy is ‘Poem Written in a Boat on the Wu River’ by Mi Fu. In this case the art is all about the method, with Mi Fu drawing each character from rotating his elbow, not his hand, and supposedly doing so in a boat. This creates distinctive lines and dark spots from his varying pressure, that expresses his method in the art, showing both artist and artpiece together.

Poem Written in a Boat on the Wu River (Circa 1100)

Poem Written in a Boat on the Wu River (Circa 1100)

The parellels in form are obvious here. Take for example the following Haskell code (from Learn You A Haskell, Chapter 10):

1

2

3

4

5

6

solveRPN :: String -> Double

solveRPN = head . foldl foldingFunction [] . words

where foldingFunction (x:y:ys) "*" = (y * x):ys

foldingFunction (x:y:ys) "+" = (y + x):ys

foldingFunction (x:y:ys) "-" = (y - x):ys

foldingFunction xs numberString = read numberString:xs

And what its form says in comparison to a Pythonic implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

def solveRPN(stack, function):

for token in function.split():

try:

stack.append(int(token))

except ValueError:

b = stack.pop()

a = stack.pop()

if token == '+':

stack.append(a + b)

elif token == '-':

stack.append(a - b)

elif token == '*':

stack.append(a * b)

return stack

The shape, size and method of these code blocks make statements on author beliefs and intentions. The choice of haskell, and the use of complex syntax to create more elegant code express the belief that code should be smart, functional and correct.

Meanwhile the Python code represents the beliefs that we should make things clear, using simple statements such as if, elif and return, and that to make code readable (and less mathematical, which you may take how you will), we should use long variable names with clear meaning.

Despite using the same medium (text, programming) the choice of tools and method express different things and produce different results. This is no different to two different caligraphers and the differing ways they choose to produce characters on a sheet of rice paper. Indeed these code blocks also encode beliefs, in the same way paintings such as Salvador Dali’s ‘The Persistence of Memory’ makes a statement on art as a medium (too focused on realism) through its existence, so too does Haskell code make a statement on programming as a medium (too focused on imperative ideas, not mathematics and purity) through its.

Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory (1931)

Salvador Dali’s The Persistence of Memory (1931)

Art As Result

Some individuals view art as all about the piece, the result. For example, the painting ‘The Fallen Angel’ by Alexandre Cabanel is a depiction of Lucifer, a deep expression on his face, having been cast out of heaven by God.

Alexandre Cabanel’s The Fallen Angel (1847)

Alexandre Cabanel’s The Fallen Angel (1847)

Here the meaning is not just in the theological statement made but in the depth of emotion, expression and beauty the piece presents.

The video game Bioshock similarly is a complete piece, whose method is not key, and whose medium (3d first-person shooters) is dull and overplayed. And yet, like The Fallen Angel depicting a new depth of emotion in art, Bioshock presents a new depth of gaming’s ability to express complex debates and discussions. The game centers around Rapture, a city hidden underwater and led by the businessman Andrew Ryan. The game explcitiy mirrors Ayn Rand’s Atlus Shrugged, and aims to create a narrative critical of her belief of Objectivism.

2K Australia’s Bioshock (2007)

2K Australia’s Bioshock (2007)

Indeed video games, a form of software, have had their own pieces that push forward the depth of emotion expressed. The Last of Us is a game about Joel, a man in an apocalypse caused by the cordyceps fungus, who has lost his daughter. He bonds with a young girl called Ellie, adopting her as a surrogate daughter, and the game sees the depths of their bond and questions what it means to be moral in an apocalypse, and in the face of love.

Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us (2013)

Naughty Dog’s The Last of Us (2013)

Alexandre Cabanel’s The Fallen Angel (1847)

Alexandre Cabanel’s The Fallen Angel (1847)

The Problem Of Money

A big critique that might be laid against this idea is that most programs are produced for money, without intention. They are made at request, in what is most efficient, for a purpose. I suggest that this does not prevent it from being art, but that instead it is in line with art’s history, and that open-source mirrors the art revolution.

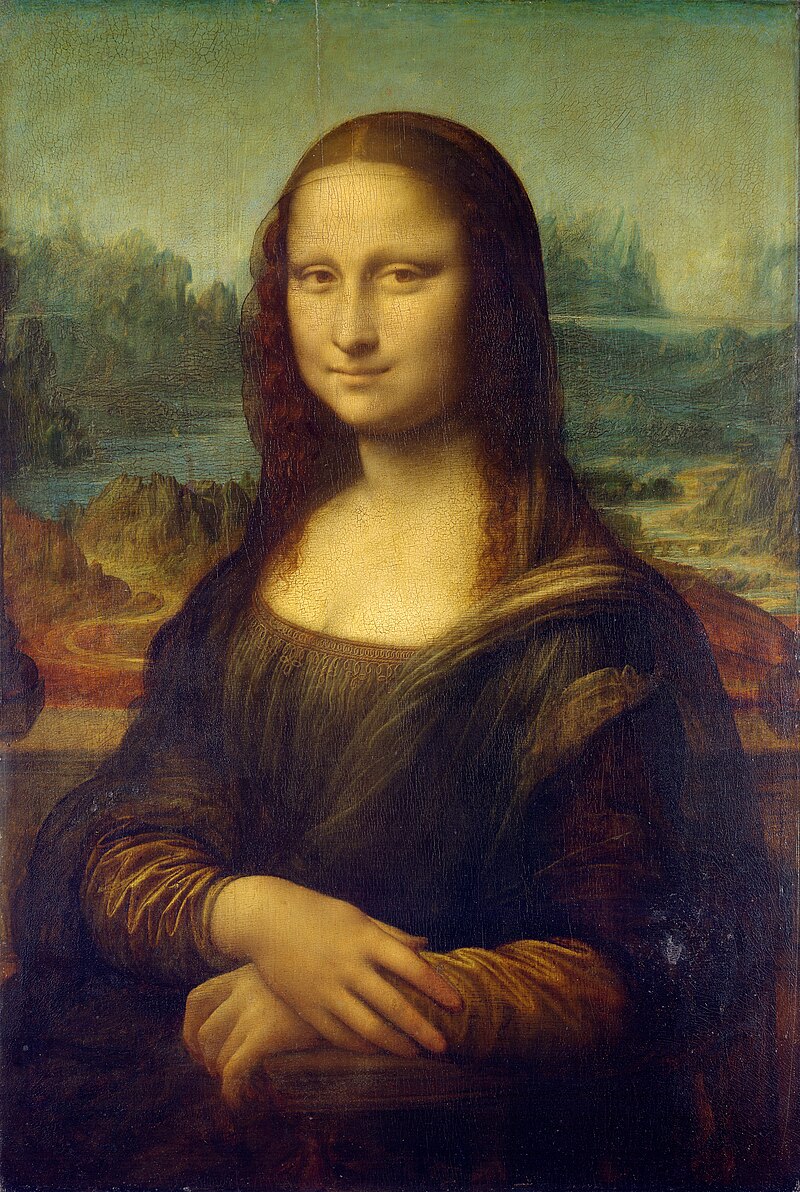

The most famous piece of art in the world, the Mona Lisa, was commissioned by Francesco del Giocondo, a wealthy silk merchant. It is likely a painting of his wife. Take a moment to consider this. The most famous piece of art in the world was created for money, by instruction, with its contents dictated. Yet we appreciate its beauty and consider it an amazing work for its form and intricacy irregardless.

Leonardo DaVinci’s Mona Lisa (Circa 1503-1506)

Leonardo DaVinci’s Mona Lisa (Circa 1503-1506)

Similary, amazing programs such as IBM’s Deep Blue, the first computer to beat the world chess champion, was made for profit, in a commercial environment. In spite of this it remains a complex interplay of hardware and software. It is a work of mathematics, software and hardware optimisation and domain knowledge. It is fair to call it a beautiful system.

Programs can make people think too :^)

Programs can make people think too :^)

Nowadays art is practiced more freely, with exhibitions paying for pieces designed by artists at their own will. Open-source software mirrors this in some ways, with people programming for their beliefs and wants, and being donated money to continue creating.

The Invention Of Photography

It is well known that the invention of photography caused a panic in the art world. People has spent centuries mastering the representation of the human form, only for a machine to do so perfectly every time with no effort. From this revolution two answers emerged and continue today, and I believe that modern programming developments may mirror this.

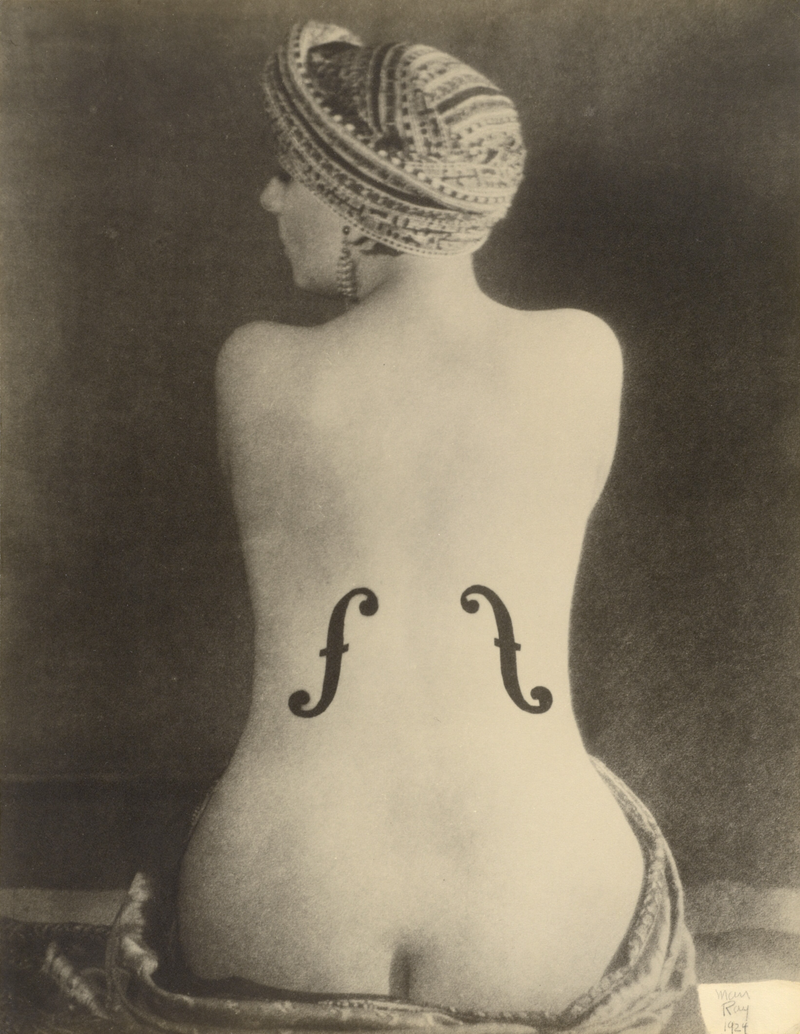

Photography As Art

Photography itself has become a medium of art, with books showing the best photos and rules for creating impressive compositions, such as the rule of thirds, carrying from art through to photographs.

Inevitably we have to discuss that today a machine threatens to replace the artist again. Large Language Models can replicate some programming a human can do, and do so much faster. People fear replacement, the death of the medium, and some see a rebirth ahead. Others see apocalypse.

But perhaps the most clear parellel to photography as art is algorithms as art. Indeed people design perfect prompts, producing better pieces of code, and can choose tools that still represent and enforce key ideas. Sometimes people work in parellel, doing business logic themselves but using LLMs as tools to scaffold, like an artist with a camera and photoshop.

Many people see this as the future, a world where LLMs and humans interact to produce programs at a faster rate than before, harboring more complexity.

Man Ray’s Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), one of the first surrealist doctored photographs

Man Ray’s Le Violon d’Ingres (1924), one of the first surrealist doctored photographs

Surrealism In Art

The other answer artists gave was to emphasise what photography couldn’t do. Works like ‘Self-Portrait (Know Thyself)’ by Rita Kernn-Larsen depict complex scenes that have deeper meaning than capturing a moment, and representing real life.

I think the programmer’s response should not be surreal, but mathematical. The choice to embrace correctness, mathematics and functional programming may provide the perfect counter to machine generated programs, as surrealism did to photography.

What made surrealism effective was the ability to do easily what photography found hard. Indeed what mathematical programs do easily is correctness, robustenss and beauty, things machine programs struggle to do. Edgar Djikstra’s ‘On the Cruelty of Really Teaching Computer Science’ argued that students should be taught mathematics a preamble to programming, and that programs should be planned and proved before being written.

Contrary to the modern ‘move-fast break things’ mantra of programming, this view emphasises perfection and correctness. Perhaps this is the correct way to move forward. Indeed it is mathematics that brought us the large language model, and near-perfect algorithms such as Djikstra’s shortest path algorithm.

By working on correct, mathematical, complex programs perhaps we can create even better works that before, and truly push the medium forward. This idea is also notable as it returns us to the core concept of a computer, such as Babbage’s Analytical engine, as devices that perform automatic mathematics.

Perhaps returning to our origins, and seeking to do better, is the true revolution.